Introduction

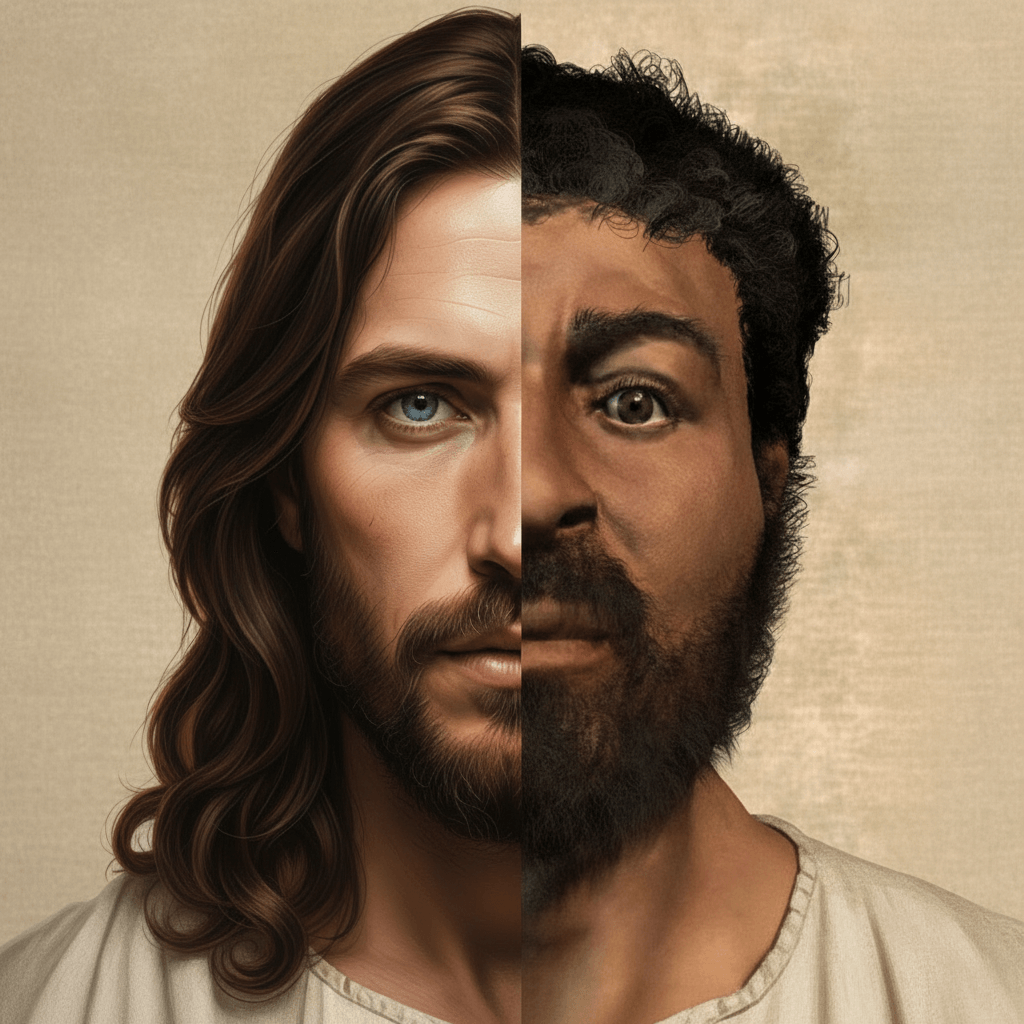

Close your eyes for a moment and imagine the face of Jesus. What image comes to mind? For the vast majority of people, especially in the West, the figure that forms is that of a man with fair skin, long, straight or gently wavy hair, a well-trimmed beard, and, often, blue or green eyes. This is the image enshrined in church stained-glass windows, Renaissance paintings, Hollywood films, and countless pictures hanging in Christian homes. It has become such a powerful cultural icon that, for many, it is the definitive representation of the Savior.

But does this familiar and comforting image correspond to historical, biblical, and geographical reality? Would a man with these features stand out or blend in among the people of first-century Galilee? The answer, supported by a mountain of evidence, is a resounding “no.” The European representation of Jesus, though artistically influential, is a historical anachronism that distances the figure of Christ from his true Jewish and Middle Eastern context.

In this article, we will embark on an investigative journey to deconstruct this popular image and seek a more authentic understanding of Jesus’s true physiognomy. Using findings from forensic anthropology, historical analysis, and clues found in the Scriptures themselves, we will assemble a composite sketch much more faithful to the “carpenter, the son of Mary.” Furthermore, we will critically examine one of the world’s most famous relics, the Shroud of Turin, to understand why modern science considers it a medieval forgery, not the burial cloth of Christ. The goal is not to diminish faith, but to strengthen it, by trading an artistic tradition for historical truth and drawing closer to a real Jesus, who walked, lived, and looked like the people He came to save.

“…he had no form or majesty that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him.” (Isaiah 53:2b)

1 – Deconstructing the Icon: The Origin of the Popular Image

The image that dominates the collective imagination—a Jesus with fair skin, long brown hair, a well-trimmed beard, and often, blue eyes—is so ubiquitous that it seems like a historical truth. It adorns church stained-glass windows, Renaissance paintings, and Hollywood productions. However, this representation does not originate from 1st-century Judea, but from Europe, centuries after Christ’s death.

The earliest artistic depictions of Jesus, found in the Roman catacombs, showed him as a beardless young man with short hair and Roman features, resembling the god Apollo or a Greek philosopher. It was an attempt to contextualize him within Greco-Roman culture.

The major shift occurred from the 4th century onwards, with the officialization of Christianity in the Roman Empire. To convey the idea of power, divinity, and authority, Byzantine artists began to associate the image of Christ with that of an emperor or, more directly, with the Greco-Roman god Zeus (or Jupiter). This is where the long hair, beard, and majestic, severe countenance, characteristic of the “Christ Pantocrator” (All-Powerful), originated.

This image was inherited and consolidated during the Renaissance. European artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, projected their own ethnic traits and ideals of beauty onto Jesus. The Jesus they painted was, essentially, a European man. This version, artistically powerful and culturally dominant, spread throughout the world through colonization and missionary work, becoming the global standard we know today.

2 – The Composite Sketch of History: What Science and the Bible Say

If the popular image is a European artistic construction, what would Jesus’s real appearance have been like? To answer this question, historians and scientists have turned to forensic anthropology, archaeology, and the clues contained within the Bible itself.

In 2001, British forensic anthropologist Richard Neave, from the University of Manchester, led a project to reconstruct the face of a first-century Galilean man. Using Semitic skulls from the era and region, found by Israeli archaeologists, his team applied forensic modeling techniques to create what is considered the most scientifically plausible portrait of Jesus or one of his contemporaries.

The study’s conclusions, corroborated by historians, point to a man with the following characteristics:

- Skin: Olive-brown, tanned by the strong Middle Eastern sun, typical of someone who spent most of their time outdoors.

- Hair and Beard: Dark (black), short, and curly hair, and a full beard, though not necessarily long, as was common among Jewish men of the time. The idea of long hair is contested by passages like Paul’s in 1 Corinthians 11:14, which considered it a “disgrace for a man to have long hair.”

- Stature and Physique: Analysis of skeletons from the period suggests an average height of approximately 5’5″ (1.65m). As a carpenter, his body would have been sturdy, muscular, and his hands calloused from manual labor.

- Facial Features: A broad face, a prominent nose, and dark (brown) eyes, which were predominant features in the Semitic population of that region.

The Scriptures themselves support this image of an ordinary man. The fact that Judas Iscariot needed to identify Jesus with a kiss (Matthew 26:48-49) strongly suggests that He had no physical features that distinguished him from his twelve disciples. He blended into the crowd. The prophecy of Isaiah 53:2, applied to Him, reinforces this idea: “…he had no form or majesty that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him.” He was not the beautiful and ethereal man of the paintings, but an ordinary first-century Jew.

3 – The Clothes and the Context: Dressing like a 1st-Century Jew

A person’s appearance is not just about their facial and physical traits, but also their clothing, which reveals their social status, culture, and routine. Historian Joan Taylor, in her book “What Did Jesus Look Like?”, delves into this aspect based on ancient texts and archaeological evidence. The Jesus that emerges from her research did not wear the long, white, immaculate robes seen in sacred art.

As an itinerant craftsman, his clothes needed to be practical and durable. He likely wore:

- A short tunic: Made of simple, undyed wool (in shades of gray or brown), which reached his knees. This allowed for mobility to walk long distances and work.

- A mantle (himation): An outer garment, also of wool, used for protection from the cold and often serving as a blanket at night.

- Leather sandals: The most common and practical footwear for the region’s terrain.

The famous “seamless tunic” mentioned in John 19:23, for which the Roman soldiers cast lots, was not necessarily a luxury item, but a type of good-quality garment. However, his overall attire would have been that of a common, rustic, and hardworking Jewish man, far from the regal and ethereal figure popularized centuries later.

4 – The Shroud of Turin: Relic or Medieval Forgery?

No discussion of Jesus’s physiognomy would be complete without addressing the Shroud of Turin, a linen cloth bearing the image of a crucified man that many believe to be Christ’s burial shroud. The figure on the shroud—a tall man with long hair and a beard—has profoundly influenced the iconography of Jesus. However, decades of rigorous scientific investigation tell a different story.

The most significant blow to the Shroud’s authenticity came in 1988, when three independent laboratories (in Switzerland, England, and the United States) performed radiocarbon dating (Carbon-14) on samples of the fabric. The results were conclusive and convergent: the linen of the Shroud was produced between 1260 and 1390 AD, in the heart of the Middle Ages. This aligns perfectly with the first documented historical record of the piece, which dates to around 1355 AD in France.

Besides the dating, other factors raise serious doubts:

- The Nature of the Image: Chemical and microscopic analyses have revealed that the image is extremely superficial, affecting only the outermost fibers of the linen, and contains particles of pigments (tempera and iron oxide). This suggests the image was painted or printed by an artist, not formed by contact with a body.

- Anatomical Inconsistencies: Experts point out that the image of the man on the Shroud is anatomically disproportionate and elongated, more consistent with the style of medieval Gothic art than with a real impression of a human body.

- The Silence of History: There is no mention of a burial shroud with Jesus’s image in the first 1300 years of Christian history. If such an extraordinary relic existed, one would expect early church fathers, historians, or pilgrims to have mentioned it. Its sudden appearance in the 14th century is highly suspicious.

Given this evidence, the overwhelming majority of historians and scientists conclude that the Shroud of Turin is an ingenious and pious medieval forgery, not an authentic 1st-century relic. Therefore, the image it presents cannot be used as a reliable guide to the true appearance of Jesus.

Conclusion

The journey to discover the true physiognomy of Jesus leads us to a clear and, for some, surprising conclusion: the Christ of history was very different from the Christ of Renaissance art. The popular image of a European Jesus, with fair skin and long hair, is a cultural and artistic construction that, while influential, does not reflect the reality of a first-century Jewish man living and working under the Galilean sun.

The evidence from forensic anthropology, archaeology, and the Bible itself converges on a more authentic portrait: a man with brown skin, short dark hair, of average height, and a body made robust by carpentry work. A man whose appearance was so common among his people that he could blend into a crowd unnoticed—a truth that underscores the depth of his incarnation. He did not come as an ethereal and physically distinct figure, but as one of us, in all his humanity.

At the same time, rigorous scientific analysis of the Shroud of Turin demonstrates that it is a medieval artifact, not a miraculous 1st-century photograph. Therefore, it cannot serve as a basis for Christ’s appearance.

Deconstructing such an entrenched icon is not meant to shake faith, but to purify it, anchoring it in historical reality rather than human traditions. Recognizing the real, Middle Eastern Jesus helps us better understand his context, his mission, and the universality of his message, which transcends any ethnicity or culture. The true beauty of Christ was not in an idealized appearance, but in his words, his acts of love, and his redemptive sacrifice—a beauty that no brush can capture, but that the heart can know.